PEOPLE has exclusively obtained four letters that 46-year-old American Sarah Krivanek addressed to loved ones back home, expressing concern for how she’ll return to the U.S. when her sentence ends.|

By Juliet Butler

Published on October 19, 2022 12:30 PM

In letters sent to loved ones back home, jailed American Sarah Krivanek writes: “my soul is in torment.”

Krivanek, 46, is serving a one-year, three-month sentence in a remote Russian penal colony in connection with domestic assault charges that stemmed from a November 2021 dispute in Moscow. She told the court that she was defending herself from repeated attacks against a Russian man she knew and nicked him on the nose with a knife.

She’d been living and working in Russia’s capital as a schoolteacher for five years when the incident occurred.

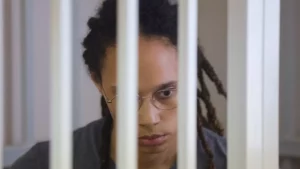

Krivanek is one of two known American women imprisoned in Russia. The other is WNBA star Brittney Griner.

The four letters she sent from the labor camp, obtained exclusively by PEOPLE, are written in Russian as they are censored by the prison authorities. They were delivered to prisoners’ rights activists who have established contact with her, acting on behalf of her family and friends.

“I am all alone here in prison with no support,” she writes in one. “I have no friends. I can trust no one! This is a very evil place.”

Krivanek says that she was permitted to make one call to the U.S. Embassy on Aug. 24 to ask why no embassy officials had come to see her since her incarceration last December.

“They promised they would send someone to see me!” she writes of the call. “I am still waiting for a ‘diplomat’ to come and visit me. I can tell them what problems I have here in the camp so they can help me with my health.”

“Please call them again,” she urges her family. “Tell them that Sarah Krivanek is waiting for someone to come to her!”

A spokesperson at the embassy told PEOPLE on Tuesday that they were aware of Krivanek’s situation but were unable at present to give a statement regarding a potential visit.

Prisoners’ rights activist Natalia Filimonova, from the NGO ‘Russia Behind Bars,’ tells PEOPLE that life in a labor camp is “10 times” worse for Krivanek, who worked as a well-paid accountant in the U.S., than it would be for the average Russian inmate.

“Sarah’s offense was very minor, but she will be in with those who have committed serious crimes like murder and drug dealing,” she says. “It is not a good contingent.”

“Also, inmates can get medical attention there with Russian insurance, but that’s only for Russian citizens,” Filimonova adds. “Sarah can’t access that or even buy medicines or vegetables, fruit and milk because her family aren’t allowed to transfer money to her from abroad.” Krivanek is also unable to communicate freely with her loved ones outside Russia as phone calls or letters abroad are only permitted under rare circumstances.

Filimonova, who arranged for a food package to be delivered to Krivanek through local volunteers as well as a visit from the Russian Public Monitoring Service, explains that it will be very hard for “a person from a different world, who doesn’t fit in and understand the unspoken rules of a place like that. She will be shouted at and humiliated for the slightest violation.”

Filimonova adds that Krivanek cannot divulge the true conditions in the labor camp because criticism of the prison regime is forbidden. “I am not allowed to write or speak in English,” Krivanek writes in one letter. Filimonova explains that this is because “something that cannot be understood cannot be censored. She won’t even be allowed to talk to herself or swear in English.”

“The main focus is not rehabilitation, but oppression,” Filimonova says. “The system is created around the need to crush you. It’s hell.”

This is borne out in one of Krivanek’s letters when she writes: “My soul is in torment and I need some peace.” She adds that she is comforted by prayer. “I pray constantly, my prayers soothe me.” She is also buoyed by her love for family and friends. Both her parents died while she was in Russia, but she has three children in the U.S. and a loved one affectionately called “Nanny,” who is like a mother to her. She also has two small grandchildren — neither of whom she has seen.

“I think about my family all the time,” she writes in one letter. “I am worried about Nanny too and I am trying to contact them constantly. I want them to know that I love them SO much. Tell them I love them madly!”

Nanny, the grandmother of Krivanek’s son, tells PEOPLE: “I love her as much and more than she could ever love me, and I think about her all the time. I have our picture sitting right on my nightstand by our bed and I look at it every night and pray for her to be strong.”

Filimonova says that women in Krivanek’s prison work three shifts, cleaning, cooking, sewing or working in the fields.

“It’s hard physical work and they are given long hours to keep them fearful and submissive.” Commenting on Krivanek’s health problems, she adds: “It doesn’t matter how sick you are, you have to work. There are no exceptions.”

Krivanek’s close friend Anita Martinez has been campaigning for awareness of her plight by writing to President Joe Biden and the U.S. State Department, with no success. She is concerned seeing that Krivanek is clearly very worried about what will happen to her upon her release. Krivanek is scheduled for deportation, which is not paid for by the Russian government, and will be kept in a holding cell until she can organize her own trip home.

Svetlana Gorbacheva, Krivanek’s former lawyer who defended her at trial, tells PEOPLE that the U.S. Embassy will be informed when it comes time for her to be deported. “It’s then up to them to help her.” Gorbacheva adds that the political situation in Russia has made it very hard and prohibitively expensive to leave the country.

“It would be great to get home before New Year!” writes Sarah. “I will probably be taken to a detention cell and then a court will decide about my deportation. Better to get home through our Government in this time of war.”

“I am waiting for a reply from you,” she says in her last letter to Filimonova, “explaining how the process will go and how I can get home. My hands are tied here in prison. It is hard for me to help myself in here.”

But, she declares at the end, “I have not yet given up!”

Nanny tells PEOPLE that Krivanek has been through many hardships in her life, with a distant mother and cruel stepfather. Although her career eventually flourished, her personal life suffered.

“She had such a beautiful house, a good income, a new car and then she got involved with this one guy in Russia through a dating site,” says Nanny. “She kept sending him money and went out twice to visit him. The third time she went, she never came back.”

According to Nanny, the Russian man she moved there for did not treat her kindly; he “spent all her money” and left her stranded there.

Nanny adds that Krivanek fell in love with her job teaching Russian kids to speak English, but privately moved from one harmful relationship to another. “She’s a giver. She was so kind and so smart, her heart is as big as it can be. But her weakness for men overrode everything. She just wanted to be loved so much.”